By Dr Jonathan Shurlock

Edited by Dr Ahmed El-Medany

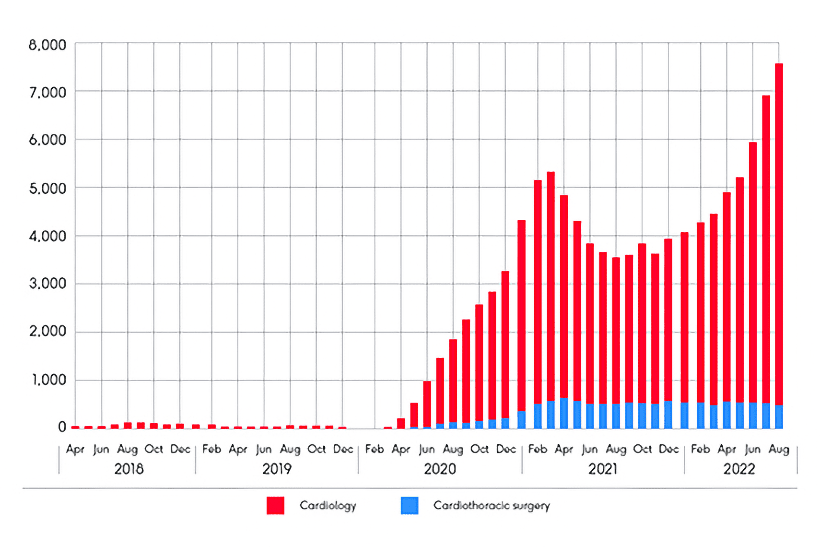

In March we reported on the British Heart Foundation (BHF) response to NHS England’s figures demonstrating growing cardiac waiting lists. At the time of that article 369,204 people were on a waiting list for ‘heart related healthcare’, a 58% rise from February 2020. BHF has now further responded to updated figures from NHSE, and it will surprise few that the figures make for distressing reading. Cardiac waiting lists have increased further, with a current record high of 392,698 individuals as of the end of May 2023. This is an increase of 68% since February 2020, used as a benchmark as the month prior to COVID related disruption.

With a worrying overall trend, a deeper exploration of individual targets yields similar outcomes. The number of individuals waiting >12 months for ‘time-critical’ investigations or treatments has risen further to a new record high of 12,468. 36% of individuals on waiting lists are waiting more than 18 weeks for their care, which is all the more stark in the context of evidence demonstrating an association between longer waits and worse healthcare related outcomes.[1]

Ambulance waiting times for category 2 calls (including suspected myocardial infarction) have also risen to 37 minutes as of June, up from 32 minutes in the preceding month. While the official target is 18 minutes, the government has adjusted this to aim for a target of an average response time of 30 minutes over the course of 2023/24. It seems that even this pessimistic and cynically adjusted target will be difficult to meet in the current climate.

There are evidently no simple fixes for worsening waiting lists, a finding likely replicated across specialities. The current environment of repeated strikes, limited long term workforce planning, and increasing healthcare needs will make addressing this difficult for the government.

References:

[1] Reichert A, Jacobs R. The impact of waiting time on patient outcomes: Evidence from early intervention in psychosis services in England. Health Econ. 2018 Nov;27(11):1772-1787